Every encounter with the natural world is a special one for me, each new creek or patch of moorland a delight to discover, but every now and then I come across a place that is particularly special.

Begwary Brook in Bedfordshire is a marshy haven abundant with life, a peaceful escape from the droning traffic of the nearby A1. As you walk the uneven yellow brick path, then continue alongside the River Ouse meandering lazily past, white tails on furry brown bottoms bob up ahead, rabbits darting into the undergrowth. You catch a glimpse of two ears, stock-still, a shiny black eye and button nose twitching as you creep past.

I first encountered the little nature reserve on a sunny evening just over a month ago. I was working away from home, only my second foray out of Cornwall since the start of the pandemic, and feeling incredibly exposed. For months I, like many people, had been cooped up in my flat, working from our old dining table repurposed into a desk. Hotel rooms, strangers, even basic human interaction, had all become well out of my comfort zone, whereas once, as an actor often away on tour, they were sometimes more familiar to me than home. To discover a nature reserve so close to where I was staying flooded my harried mind with relief.

Stepping in through the trees, I took care to stick to the path, avoiding the water-logged grassy areas either side. Used to Cornish clifftop coastal paths, this flat, marshy terrain was foreign to me, unfamiliar yet enticing.

Up ahead the grass gave way to water, still and slick, reflecting the bare branches above. Early to leaf, willows dipped graceful tendrils into the pool. The path ran alongside, sitting water on one side, the flowing water of the river on the other. A kayaker glided past.

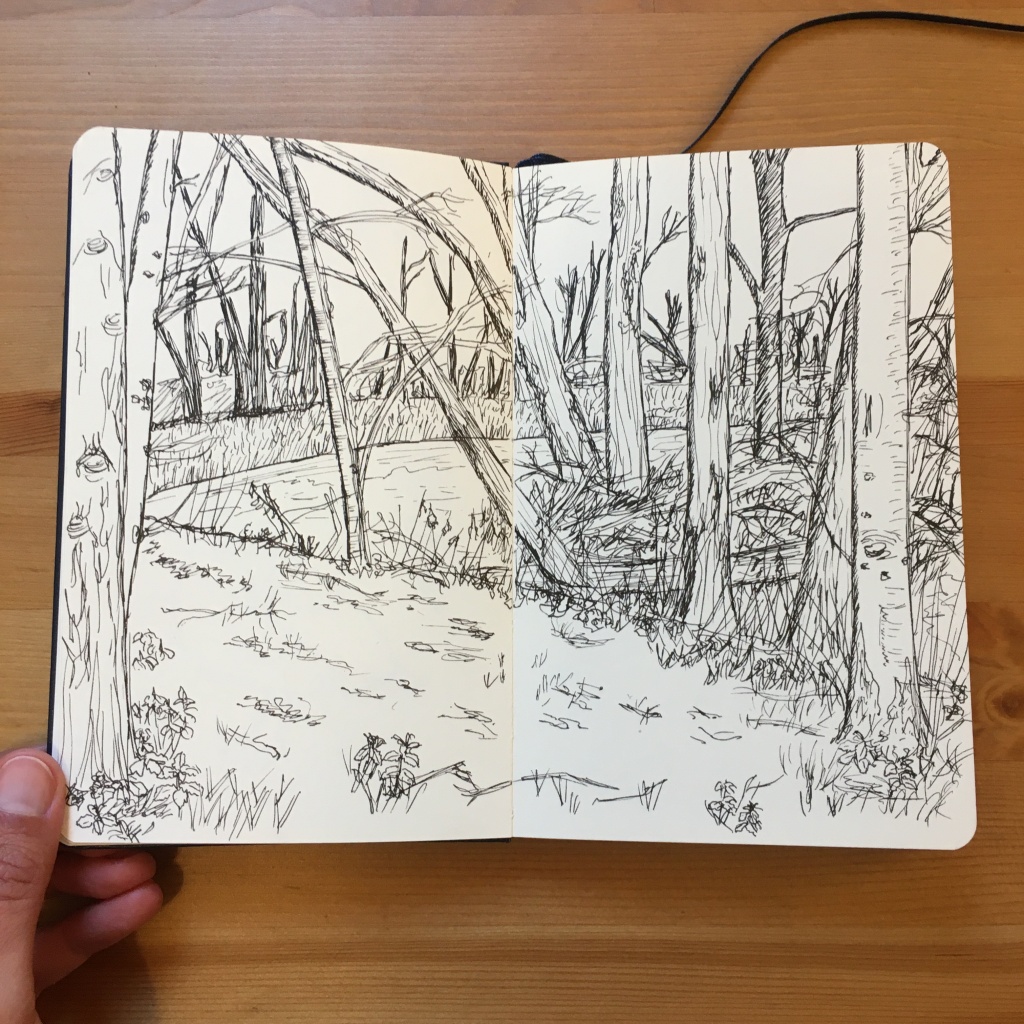

Leaving the glassy pool behind, the vista opened out before me, a spread of marshland. Trees rose up out of the marsh, some with thick, sturdy trunks, others clawing dead fingers at the sky. Many in the wooded areas had fallen or stood bent at the waist, supported by the trunks of their neighbours. Clumps of nettles bordered the path, dry scratchy grasses breaking through rich green foliage bordering the marsh. This mixture of wet and dry, of lush greens and parched browns, of messy undergrowth and still, swampy water was a different world to my home in Cornwall. But it was beautiful all the same, and bathed me in a wonderful sense of peace.

Following a topsy-turvy path, I meandered through the trees. The percussive trill of a woodpecker travelled through the wood. I stopped and pricked up my ears, desperate for another hint of its presence. It came again.

Out in the open again, a bumble bee bustled past and a pale yellow butterfly danced around my head. All around me, the nature reserve was teeming with life, much of it remaining hidden from human sight.

I returned to this special place whenever my work schedule permitted over the following two weeks. The giddy energy of that first sunny encounter was replaced by a contemplative stillness on my next visit, the sky a blanket of dusty grey clouds and the air a touch cooler. I delighted in discovering the changing character of this place each time.

There are two moments from my walks around Begwary Brook that are particularly special to me. On one occasion I was stomping happily along when I narrowly missed stepping on a toad. It stood stock-still on the path, its knobbly brownish-green body blending with the earth. After forcing aside the initial distress that I almost squashed the little chap, I took a moment to mark this special encounter, then carefully stepped past to leave it in peace.

The second notable moment came a week later. I was walking the opposite way around the reserve to get a different perspective, and had stopped to enjoy the birdsong, when I spotted an animal on the path up ahead. We were too far apart for me to make it out clearly, but I saw a deer’s head on a shorter, stockier body than I expected, about the size of a medium-sized dog. As part of my mind struggled with these unfamiliar proportions, I stood mesmerised. I watched this creature as it stood watching me back. And then it was gone.

I recounted the experience to my mum that evening and she suggested it could have been a muntjac deer. Never having heard of this, I dutifully Googled and discovered this species was introduced into the UK from China in the 20th century and is now commonplace across South East England. Protected in the UK under the Deer Act 1991, it can however cause damage to woodland through browsing. Looking at the images on my screen, I was sure this was what I’d seen. An encounter with a creature I hadn’t even known existed!

I don’t know why Begwary Brook feels so special to me. Maybe it’s because it provided a safe space to feel close to nature when I felt otherwise exposed and scared about the pandemic. Maybe it’s because it felt like a home from home – a very different type of habitat to home, but the natural world nonetheless. Or maybe it’s because that’s exactly what it is: a very special place, and one I hope to return to one day.